| ||||

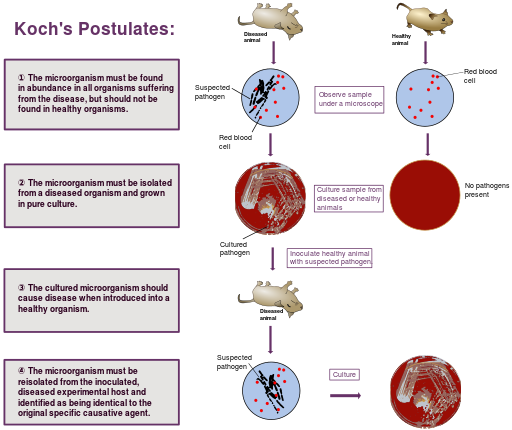

Koch's Postulates:

Scientific Method Linking Microbe to Disease

CLASS NOTES from Science Prof Online

While working as a physician, Robert Koch (pronounced “Coke”), began investigating a mysterious disease that was decimating livestock populations and causing illness in humans as well.

Koch’s Investigation of Anthrax

The illness that interested Dr. Koch was known to quickly kill afflicted animals, turning their blood black. Koch examined the blood of the diseased animals and found that it contained long strings, which, when viewed through a microscope, were found to be growing,

Article Summary: In the late 1800s, German physician Robert Koch formulated the series of steps required to prove the cause of any infectious disease.

Koch's Postulates

Dr. Robert Koch (1843 - 1910)

You have free access to a large collection of materials used in a college-level introductory microbiology course. The Virtual Microbiology Classroom provides a wide range of free educational resources including PowerPoint Lectures, Study Guides, Review Questions and Practice Test Questions.

Page last updated:

8/2014

SCIENCE PHOTOS

| ||||||

| ||||||

SPO is a FREE science education website. Donations are key in helping us provide this resource with fewer ads.

Please help!

(This donation link uses PayPal on a secure connection.)

SPO VIRTUAL CLASSROOMS

dividing, living organisms. These strings were eventually found to be a type of bacterium later designated as Bacillus anthracis.

Anthrax bacteria is a pathogenic rod-shaped microbe that has the ability to form endospores — structures that can be thought of as bacteria “seeds” — which remain dormant and resistant to destruction until, under the right environmental conditions, they germinate into living bacteria. However, the mere presence of these stringy bacteria in the dead livestock was not sufficient evidence to prove that the bacteria actually caused the disease affecting the animals.

Obtaining Pure Cultures of Microbes

When investigating the infectious diseases anthrax, and later tuberculosis, Koch had to find a way to demonstrate a definitive cause-and-effect relationship, in each case, between the suspected microbe and the disease. In order to do this, he had to first obtain a sample of the microbe from an animal that was thought to have the disease. Since biological samples may contain numerous types of bacteria, both beneficial microbes and sometimes pathogens, the different types of microbes in the biological sample had to first be separated.

This was done by spreading the sample onto a growth medium, such as a potato slice or the gelatin agar that Koch invented for this specific purpose. The individual bacteria would then begin to grow on the medium, each cell dividing, through the process of binary fission, until a bacterial colony was visible. A colony is a large number of bacteria that have all arisen from the same parent cell, and are therefore all related, and of the same type.

Then, of all the isolated bacteria, the type suspected of causing the disease had to be found and grown in a pure culture containing only that kind of bacteria. That pure culture could then be tested using Koch's postulates.

What Are Koch’s Postulates?

Koch first explained his method to the scientific community in articles he published on tuberculosis in the late 1800s. The postulates are as follows:

- A microbe suspected of causing a certain disease must be found in ever case of that disease.

- The suspected microbe must be isolated and grown in the laboratory, outside of the host.

- When this suspected pathogen is introduced to a healthy, susceptible host, that host must develop the disease.

- That same pathogen must then again be obtained and reisolated from that experimental host.

The microbe of interest in the investigation of an infectious disease is always considered to be a “suspected pathogen" until it has been tested, and has fulfilled the requirements of the four postulates, in order, one through four. Koch’s postulates work so well that they are still the scientific method used in infectious disease research to this day.

Sources & Resources

- Bauman, R. (2014). Microbiology with Diseases by Taxonomy, 4th ed., Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

- Leboffe, M. J. and Pierce, B. E. (2010) Microbiology Laboratory Theory and Application, Third Edition. Morton Publishing Company.

- Perry, J. and Stanley, J. (1997) Microbiology Dynamics & Diversity. Saunders College Publishing.

- History of Microbiology Lecture Main Page from the Virtual Microbiology Classroom.

- Isolation Streak Plate Technique "class notes" article from SPO.

The SPO website is best viewed in Google Chrome or Apple Safari.